Friday, February 19, 2010

The Invasion

Wednesday, February 10, 2010

My Friend Alphonse

Saturday, February 6, 2010

In Passing, Remember (Continued) Notes re the monument

In Passing, Remember (Continued) Mort Pour La France/Died for France

In Passing, Remember, Part 4

MORT POUR LA FRANCE/ DIED FOR FRANCE

Thus, after fifty years of history, nothing more human exists on this land battered by the cold winds of winter or the hot breath of the winds of summer.

Alone, among the ruins of old pieces of walls, some lizards scoot about, sometimes encountering a viper warming itself in the sun. The birder is king, but there aren’t many for there exists no longer a speck of water.

In returning to Nevers, passing Moiry, you see on the right a tombstone of rock terminating in a pyramid, just on the border of the road. This little monument was erected to remember that at this place was the cemetery. On the front one can read, “Aux Américans morts pour la France le Droit, la Liberté (1916-1918) (To the Americans who died for France, Right and Liberty)

Rare are those who stop a moment in memory of these allied soldiers who came from so far and who had made the sacrifice of their young lives for the freedom of France.

In Passing Remember Part 5

How Does One Commemorate the Fiftieth Anniversary

In remembering some 2,000 soldiers having slept their last sleep 50 years ago ( now 90 years ago )in this corner of the Nivernaise earth, who will go to bring a simple bouquet of flowers? Will there be only a bouquet of flowers from the fields ( this one for the soldiers who died as heroes, at the foot of this stone monument, poorly maintained and totally abandoned)?

For sure, the bodies were disinterred and transported to Nevers shortly after the Armistice, but there is still something shocking. The egoism of me continue to manifest itself, some forget quickly, to quickly even, others never acknowledge that such a forgetfulness might happen to the grand day, especially those who had survived the tragedy of the second world war.

Friends, readers, this is a story of the camp called St Parize le Châtel, but in reality, called American Hospital of Mars-sur-Allier because of the railroad serving it leaving from this station. And while you are stopping before this monument think of these soldiers who died in the dawn of the life and think about it as the poet recalling to you these simple words, “In passing, remember...’’

Editor's note: M. Wilrich was instrumental in getting the monument cleaned up initially. As written before it is now in good shape and has an honored spot in the cemetery in St Parize le Châtel. M. Wilrich bemoaned the fact that those who died here were forgotten but now the village remembers. My mother Rebecca Goethe DeVries forecast this in her article in La Montaagne in response to the above article in her wish that the monument be honored in the future on the American Memorial day. This happened Memorial Day weekend, 2001. My family and I put flowers on the monument in memory of the American soldiers who died there and in memory of my parents. I spoke at that event and now each Memorial Day M. Gianni Belli asks me to send a few words to be read at the ceremony of remembering. The village remembered with a grand celebration and exhibition on November 11, 2008.

Translation and note, copyright, Lucy DeVries Duffy, 2/5/2010

In Passing, Remember (Continued) Some German Prisoners

SOME GERMAN PRISONERS

Besides the American soldiers there were naturalized Americans, those Greeks, Italians, Spanish, even German, having emigrated to the United States, and volunteered for the duration of the war. There were also wounded German prisoners who lived in the enclosure of the camp and took part in the same life as their guards.

Toward the end of the war, there were many wounded arriving from the front. As the place was inadequate, the later arrivals were cared for in the trains which brought them.

As soon as the state of their health permitted it, the convalescents were authorized to go out and walk, to make a tour in the villages around.

For the local population it was a windfall to have a military camp so near, for the United States did not fail to furnish copiously their soldiers with foodstuffs, conserves, etc.

And when the camp was closed, when the soldiers were evacuated, there was a grand debauch of the American surplus, which finally gave back supplies to people deprived of things from the war.

However, during the activity of this military city, many of the people were employed there in the services of governing and administration.

In Passing, Remember (Continued) Always More Wounded

ALWAYS MORE WOUNDED

As bit by bit the number of wounded grew, it was necessary to build new barracks. The material, stone especially, was taken from the quarries located near Moiry. A good number of Portuguese, Spanish and Annamites were employed there. ( Note: Annamites were Vietnamese.)

In spite of the care given to the wounded, many died. It was then decided to build a cemetery, very rudimentary - similar to those of the front --. This cemetery was built at the south west side of the camp in a big field slightly inclining, terminating along the side of the national route 7.

In the course of the winter 1917-1918 many of the workers, Spanish and Annamites, employed in the different services of the camp, as well as the soldiers, of whom many were black, perished from the Spanish flu. The sanitary services were overflowing. The cemetery took on disturbing proportions.

In Passing, Remember (Continued)

LITTLE BY LITTLE IT ALL CAME TOGETHER

Here and there, numerous ruins of old pieces of wall, of cement paving covered with moss, the remains of smokestacks, etc...

Of numerous black thorns, eaten away by lichens, growing more and more, covering up little by little that which were these buildings.

At the beginning of the existence of this camp, some soldiers of the American Corps of Engineers came first, with little equipment -- Little by little the organization developed. -- The land was divided into squares and then were built many barracks with walls of brick, setting on floors of cement, covered with boards which were protected with tar paper. Many roads crossed the camp permitting access to the barracks and to the secondary services.

According to eyewitnesses having known this little military city (more than 45,000 people at the end of 1918!) the hospital had many blocks. Each block had around 25 barracks, placed in two rows. facing each other. Between each row were the refectories, the kitchens, the bath rooms and the w.c., the surgical block and the infirmary.

There was also a big recreation room where resident soldiers ( actors or professional comedians), singers, etc. gave their performances to entertain the convalescents. Also, the hospital was composed of many secondary hospitals. At the entrance were the general quarters - with the services of administration and the supply depots of every sort.

Evidently, militarily speaking, each block had a number in order. From the numbers 1 to 50, the blocks were housing the American Red Cross - the numbers under 50 belonged to the American states.

For this era, things were very modern. Electricity was created there, running water functioned marvelously and, moreover, in an area so dry and without natural advantages, all was quickly taken care of.

With their enormous technology, with machines and materials, the American builders went to acquire a water supply at more than six kilometers away, in the Allier River, just opposite the church of Mars-sur-Allier.

Fishermen who frequent the banks of the river could see still the wells which were dug and which still exist. The pumping station is there. The water was brought by underground ducts up to the end of the plateau to supply the camp. It was kept in reserve in an enormous water tower ( chateau d’eau), still held up by nine pillars made from the quarry of Moiry. On the facade bordering the road one can see the American insignia ( insignia of the American Corps of Engineers) fixed in the masonry.

Mar-sur-Allier American Base Hospital, In Passing, Remember

“In passing.......remember’’

Part 1

LA MONTAGNE-SUNDAY, 11 AUGUST 1968

(I have translated the following article, written by M. Wilrich, a resident of Moiry, now deceased about the Mars-sur-Allier American Hospital which was published in La Montagne, a newspaper of the city of Nevers in France in 1968. The article, written in commemoration of the 50th anniversary of the Armistice of the Great War of 1914-1918, tells the story of the huge hospital built near Nevers in 1918. Nevers is 14 kilometers north of Moiry, the hamlet where my mother, Rebecca DeVries (born Goethe), grew up. My father was a medic stationed at this Mars-sur-Allier American Hospital which encompassed the village of Saint Parize le Châtel as well as the hamlet of Moiry. It was there that my father, Charles De Vries, met my mother, Rebecca Goethe, giving this whole story a special relevance. I have entered photos and notes to M.Wilrich's article.

VISIT TO THE MEMORY OF AN OLD AMERICAN HOSPITAL

OF MARS-SUR- ALLIER

It was already fifty years since our American allies, entered into the war against Germany in 1917, came to create a military hospital in the countryside between the Loire and the Allier Rivers - Parize le Châtel - exactly at the place called “Les Gaillères’’ on the territory of the village of Saint-Parize-le Châtel - or more exactly, on the plateau of Saint Parize.

They chose this spot certainly because of the proximity to the National Route 7 and of the railroad line Paris-Nimes ( the line of the Bourbonnais from the time of the P.L.M. network.) -- permitting connections as rapid as possible with the front -- and also because of the great restful calm of our countryside then not at all busy as it is today.

IS IT SO LONG AGO

Among all the people who come to the Motor-Stadium Jean-Behr, built some years ago on a part of the terrain there where existed, a half century ago, the American Hospital, few know its history.

Thanks to numerous memories collected from people having known or even worked as civilian workers, we can tell you its history.

When you come from Nevers, in the direction of Moulins-sur-Allier, having left the village of Magny-Cours on your right, you find, about one kilometer further, to the left a little road indicating the race track Jean-Behra and the Agricultural School.

(Note: this has changed since 1968. There is now the huge race track, Le Circuit de Magny Cours)

Straight and to the left of this road you see to the left some cultivated fields and to the right a large deserted expanse, wild, interspersed here and there with cultivation but where dominates in great abundance dense thickets of black thorns, of moss, of lichen and of wild grasses, scarcely a place to nourish sheep.

The part the most interesting of the placement of this military hospital is included in a vast triangle having for a base the route national 7 and the two sides delimited on the left side by the road Magny-Cours/Saint-Parize-le Châtel, and, from the other side, by the road Moiry/Saint Parize-le-Châtel. These two routes join at the west entrance of the last village at a place called, “La Croix’’ - not very far from the town hall of this town, of which we have already spoken of its church and its crypt, the sparkling water fountains, etc., etc...

In walking in this vast triangle, one finds many vestiges recalling that in this place lived some years some allied soldiers from across the Atlantic.

The Feast of Saint Jean the Baptist

The Feast of Saint John the Baptist

This year my brother Robert is thirteen years old and it is time for him to earn his bread. On the 24th of June he is going to the traditional Feast of St. John the Baptist at St. Parize le Châtel, a near-by village. There the farmers who are looking for servants and the young people looking for work will assemble on the public place in the front of the church after the service of the Mass.

First, the Town Crier comes and beats his drum to obtain silence and give the order and the news of the day. After that, the farmers look for servants and the young people look for someone to hire them. Like a Street Fair, there are booths and a Merry-Go-Round and the people walk about and laugh a lot.

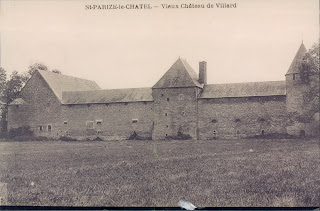

Robert is getting anxious for he is small and no one has hired him yet. He would like to be a horse driver, but my father thinks he is too young for that. He tells us that he would be better as an ox driver or a shepherd. After this he is hired almost at once by the manager of the Chateau de Villars as an ox driver. The farmer gives him a gold piece of ten francs, which is a gift and also a pledge that he will not accept any other offer.

After this is settled we relax and sit at an outdoor table. Our parents have some wine and as a special treat, we have each a chocolate éclair. Soon after, we walk back the three kilometers to our village, a bit

tired and silent.

I feel sad, for tomorrow Robert will be a man and will leave to take up his work at Villars. That is the end our good times together, our quarrels, our escapades. It is for both of us an “adieu’’ to childhood.

Rebecca Goethe DeVries

Editing and Copyright: Lucy DeVries Duffy, June 25, 2009, Brewster, MA, 02631, USA

Wednesday, February 3, 2010

Chateau de Villars where Robert worked as a bouvier

Locating Moiry/Saint Parize le Châtel in France

The Essential Thing - La Chose Principale

The Essential Thing

How many times in my childhood have I heard this short sentence, “Quelle est la chose principale?’’ “What is the principle thing?’’ “What is the essential thing?’’ would probably be a better translation.

One cold winter night this short sentence took on a special meaning for me when my brother Robert appeared at our door carrying on his back a big bag containing all his possessions. He looked so sad, so that we knew at once that something was wrong. It was a week day and he only came on Sundays to bring his laundry and spend a few hours with the family.

Entering the house, he let his bag fall on the floor with such an air of discouragement and despair that this young boy of 13 looked suddenly old. He sat down and began to cry, but so hard that his whole body shook with sobs. Mama tried to comfort him. She, too, cried without knowing the cause of his distress.

At last, he calmed himself enough to say between sobs, “Je ne suis plus bouvier à Villars.’’ “I no longer tend the cattle at the Villars farm.’’ Here in this short sentence was so much despair that Mama did not say anything. She waited for the explanation of this great misfortune, for to lose one’s job so suddenly in the middle of winter was bad. After calming down, Robert told us that since he started to work at the Chateau de Villars, the horseman at the farm had tormented him steadily.

It was one thing after another. Robert had never spoken of it hoping that this man would tire of teasing him. But Etienne, the horseman, had continued to make life difficult for Robert. His narrow bed under the stars was often full of thistles. His soup was often so full of pepper that he could not eat it. His tools disappeared or were broken. And worst of all, this very afternoon Robert had found his best aiguillon broken and thrown in a ditch. An aiguillon is a long sharp stick which is used to prod the oxen and encourage them to work. “Such a beautiful aiguillon, Mama! I have carved it myself and decorated it and put my name on it.’’ This last insult had provoked this crisis and Robert had put his oxen in the stable, packed his bag and left.

It was time for supper and Robert, in spite of his sorrow, ate heartily the good potato and cabbage soup, the good bread and cheese, and even a glass of wine to give him courage.

Mama then asked Robert, “Did you feed your oxen before leaving?’’ Robert was ashamed and blushed. “No, Mama, I wanted to leave right away.’’ Mama said, “That is not good, for your animals count on you. They are your duty. Take your bag, my boy. We’ll go with you up to the approach of the Chateau. As for this Etienne, you’ll be in your right to speak to your boss. He is a just man and will know what to do.’’

By this time, there was a full moon. It was very cold but it was pleasant to be outside and we were well wrapped in our warm coats as we walked through the sleeping village. I always liked this narrow road which ends at the Chateau. This road which was built by the Romans has large white pavement blocks and has endured all these centuries.

We do not speak and the only noise is that of our wooden shoes on the stony road and the regular barking of the farm dogs who seem to smell us. Arriving near the Chateau we stopped and Mama, putting her hand on Robert’s shoulder, looked at him tenderly and said, “You see, Robert, in life the main thing is to do one’s duty. True, there is injustice in the world, but when one does one’s duty, there is no regret. Hurry, your oxen must be very hungry. The willows have many branches and you have a good knife to make another aiguillon. Kiss us good-bye and bring your laundry next Sunday and I will make you a good galette.’’ Robert shifted his bag to his other shoulder and turned towards the farm.

Translation: Rebecca Goethe De Vries

Edited and copyright: Lucy DeVries Duffy, May 12, 2001, Brewster, MA, 02631, USA

The Chateau de Villars, ancient Château (XVI century)where Robert went to work at age 13.

Rebecca's Introduction to her Vignettes

Introduction

Vignettes of Moiry

Ladies, Gentlemen and Dear Friends.

I hope for a few moments to transport you to the village of Moiry in the department of the Nièvre , France where I spent the first years of my youth. I will call these little stories, Vignettes of Moiry.

As an introduction to these vignettes, I present this beautiful passage taken from the book The Brothers Karamazov of Dostoyevsky:

You ought to know that there is nothing stronger or best for life than some good memories, especially those of childhood. People speak much of your education but some good memories sacred, preserved from childhood are perhaps the best education. If a man carries many such memories with him all of his life, he is safe until the end of his days and if someone has only one memory in his heart, even this memory can have the gift of saving him.

Rebecca Goethe DeVries